How the rebels behind scholarly publishing app Mendeley—once labeled sellouts—are growing their company after being acquired by Elsevier.

In 2013, when Victor Henning announced that his six-year-old startup Mendeley would be acquired by one of the world's biggest media companies, he knew there would be blowback. He just couldn't have anticipated how bad it would get.

"Seeing that some of our most vocal advocates thought we had sold them out felt awful," Henning said recently over a tea in Amsterdam, where Elsevier, Mendeley's parent company, is headquartered.

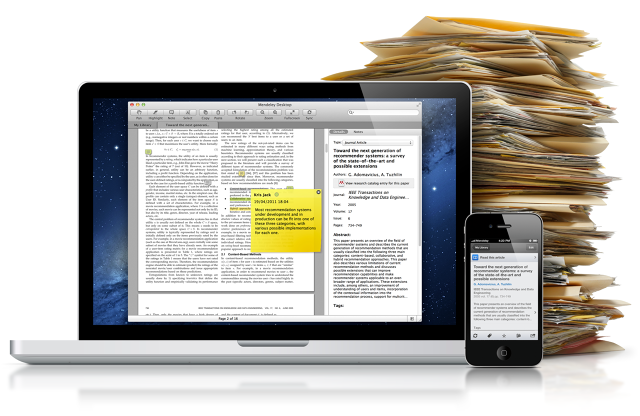

Launched in 2007 by Henning and two friends at graduate school, Mendeley built an unlikely but very useful piece of software—think a variation on Evernote combined with Facebook—aimed at helping researchers organize their papers, annotate them, and share them with each other.

It swiftly took the academic world by storm. Researchers loved the ability to search for and in some cases access papers from journals they didn't subscribe to—a small protest against the billion-dollar industry that critics insist serves as a gatekeeper to the world's scientific findings. Within a few years, Mendeley had become an icon of the "open science" movement.

Enter Elsevier, part of the Dutch publishing conglomerate Reed Elsevier, it's one of the world's "big four" academic publishers. Amid challenges in other media sectors—and as academic library budgets shrivel up—these publishers have found a way to make handsome profits. In 2014, Elsevier listed a profit of $1.1 billion on revenues of 3.1 billion, largely by selling individual research papers and journal subscriptions.

Digital sales now make up two thirds of those profits, and by 2011, Elsevier had already begun mounting its own giant digital initiative. But it lagged behind in technology. And, like other large publishers, the company loathed Mendeley's open model; In 2013, it had forced Mendeley to remove its titles from its database. The thinking behind its acquisition of Mendeley—for a sum rumored to between $69 million and $100 million—was simple: to squash the threat Mendeley posed to its traditional subscription model, and to own the ecosystem that Mendeley had constructed, with its valuable data on the behavior of millions of researchers.

The purchase inspired revolt among its users. Mendeley was branded a sellout. Sean Takats, a professor of history and media at George Mason University and a director of Zotero, a Mendeley alternative that's popular among open science advocates, said the acquisition was akin to heresy. "I have nothing against making a buck," Takats told me. "But how can you partner with someone that's closed-science?"

When it came, the criticism stung Henning especially hard; even his former director of R&D, who had left the company shortly prior to the acquisition, joined in the chorus.

"I had steeled myself for some pretty violent reactions beforehand," Henning said. "After all, I was aware of Elsevier's reputation and the mistakes they had made."

Just a year earlier, thousands of researchers, led by Cambridge mathematician Timothy Gowers, boycotted Elsevier for lobbying Congress to keep research locked up behind paywalls for good, and for profiting from "the free labor of [researchers] and subscription fees from their institutions' libraries, for a service that has become largely unnecessary."

That service has helped Elsevier become one of the "big four" of academic publishers. Representing 3,057 journals, Elsevier is second only to recently merged Springer and Macmillan (which oversees the Nature publishing group) in terms of how many titles it controls.

For Elsevier, Mendeley's walled garden is a valuable new ecosystem, offering a lens into what researchers are working on and what papers they're looking for, and becoming a funnel, in essence, to sell more licenses to researchers, libraries, and academic institutions. In its latest annual report, published in March, the company highlighted "social collaboration through Mendeley" as it announced aims to use more data from Elsevier products, as well as third-party and customer data, to "expand content coverage" and "to increase content utility."

That arrangement, critics say, has led Mendeley away from the open science principles that it once symbolized. And now, full texts of paywalled research no longer circulate freely across its network, except within private groups.

"Once social networks start to get acquired or evolve, then you end up with a system where a large organization runs a 'walled garden,'" said Peter Murray-Rust, a lecturer at the University of Cambridge and an advisory board member at the Open Knowledge Foundation. "You can only get in or get information out by asking permission from the person who owns the garden. Mendeley was and is a walled garden."

Henning, however, insists he remains determined to meet the needs of a community that thrives on sharing ideas. He points to a revamped API that allows researchers to plumb its database, which is still available under a Creative Commons license. It now incorporates research from Elsevier's catalogs that Mendeley was once forced to remove. "We've kept the promises we made when we began," Henning contends.

"Our Relationship Was Schizophrenic"

The acquisition has taken the pressure off Mendeley to monetize, and helped keep the service free for individual researchers. It's also made possible long-awaited features, like improved recommendations and search, as well as an Android app.

And Mendeley keeps growing. Its user base—as of this week, at 4 million people worldwide—still uploads 1.6 million articles every day, with 100,000 new users joining every month, the company said. It counts Stanford, Harvard, and MIT as some of its big, institutional customers, and has doubled the size of its technical team, from 40 people to 85.

Still, even once it joined Elsevier, Henning admits, things weren't smooth sailing. He and the top of the Mendeley team worked hard to find allies within Elsevier to back his company's vision for open science. At 35, Henning is probably one of the youngest people working in the upper echelons of Elsevier, where he and Mendeley have had to prove they were more than just the "new kids." (In February, amid slightly lower year-on-year profits, the company announced it would "simplify its corporate structure.")

"Our relationship with Elsevier was schizophrenic," Henning said. "They had asked us to take their papers down from our network. But they sponsored several of our early events. They were supportive of us," he said.

In recent years, the publisher has been trying to retreat from its harsh image. The behemoth backed down on its support for proposed paywall-protecting legislation. And it has increased the number of open-access journals in its offering that people can read for free, but not any more significantly than other publishers' efforts. Henning also pointed to Elsevier's recent push for an industry-wide policy for publishers to allow sharing of copyrighted material within user groups on collaboration networks, as Mendeley does.

Long before big industries blamed the web for disrupting their business model—and before startups praised it for the same reason—scientists embraced it for its original purpose: to help researchers collaborate across borders and oceans, and create a repository of information that could be easily shared and searched. "Often," wrote Tim Berners-Lee, then an engineer at CERN, in his initial proposal for a World Wide Web, "the information has been recorded, it just cannot be found."

Nearly 20 years later, Henning and two classmates at the German Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, Jan Reichelt and Paul Föckler, noticed a similar problem: Research was largely siloed, and collecting it and sharing it was difficult. "I was looking at things from psychology, business, and philosophy," he said. "My advisor had to sit me down and tell me to stay focused on one thread of research and leave the other stuff as background knowledge."

In the beginning, Mendeley's biggest draw was that research groups could chat together in one place, share articles, and easily write papers together. It fostered collaboration in the cloud. In addition to allowing papers or their abstracts to be shared freely, Mendeley managed the entire workflow of researchers' existence more elegantly than anything had before. Researchers could access their profiles no matter which workstation they used, syncing their literature and notes to the cloud, much like Dropbox does now.

And Mendeley's open API—the first in the industry—freely offered metadata on the millions of papers that its users upload to the software, like titles, authors, keywords, and references. That allowed users to easily search through its database of papers, and allowed developers to do interesting things with that data. In 2010, this was a fresh, Web 2.0 idea in an industry that didn't have many of them.

Henning aggressively built a userbase by reaching out to open science advocates in the blogosphere and holding events where he preached a vision of making all types of research available to more people. Mendeley introduced new monetization strategies, like monthly fees for user groups and an institutional edition for entire universities, and raised funds to create the slick piece of software that it is today; investors included the backers behind Last.fm, Warner Music Group, and one of the founders of Skype. In just over four years, Mendeley raised about $12 million. In 2011, Mendeley had 800,000 users worldwide. By 2013, that number surpassed 2 million.

The grand hope was that big paper-sharing, social networking startups in the open science field—Mendeley but also sites like Academia.edu and ResearchGate—could eventually topple big science publishing stalwarts like Elsevier, much like the spread of MP3s had done to the music industry.

The publishing industry was not amused. In 2010, David Crotty, senior editor of Journals at Oxford University Press, marveled at Mendeley's "apparent naïveté towards copyright law." Keeping copyright-infringing papers off the service would be the right—and profitable—thing to do, he wrote, especially if Mendeley hoped to officially partner with universities. "It's not as sexy a path as being a Jolly Roger-hoisting rebel, but no one ever said that growing up was easy."

Open access advocates aren't pirates, they insist. Their aim, they say, is to accelerate the dissemination of important findings by removing the barriers that journals and their publishers put up.

"Open science is the process of designing your experiment in the open, recording everything openly," said Murray-Rust of the Open Knowledge Foundation. "Anyone with an interest should be able to take part. Ideally, anyone in the world could access a researcher's methods, materials, and findings. This can be done through an open social network, one that's not controlled by a commercial organization."

The bigger Mendeley got, the more scrutiny it got. Under the pressure of Elsevier and other big publishers, Mendeley had to scale back how openly research could course through its channels. Eventually the company removed Elsevier's abstracts from the API, as well as its PDF previews in its software.

Jason Hoyt, Mendeley's former head of R&D, didn't agree with the moves and left in 2013, explaining his move in a blog post. He would go on to start a family of open-access journals, called PeerJ, with the backing of venture capitalist Tim O'Reilly.

"There's a bit more to the story of why Jason left than he let on in his blog post. Either way, our relationship now is fine," Henning said. "We didn't have to 'justify' taking [Elsevier's data] down. After all, Elsevier owned the copyright, and we had to comply."

Three years later, the publishing giant came calling again, this time to buy. Henning was just 32. "It came to a point where such a large amount of our papers and data was connected to Elsevier," he said. "Our business was so closely tied with theirs."

Mendeley's investors were eager too. Sean Takats, who oversees Zotero, concedes that a corporate buyout was most likely Mendeley's best option to stay afloat. "The 'business model' could never continue on its own, let alone withstand the scrutiny of a public offering," he wrote at the time. For Mendeley, he wrote, "Acquisition was always the exit strategy."

In a blog post at the time in which he defended the acquisition, Henning wrote, "The opportunity to give our users access to better content, more data, and faster development was just too exciting to pass up." Elsevier "struck us as one of the most innovative and tech-savvy publishers out there." Olivier Dumon, managing director of academic and government markets for Elsevier, told The Times of London that "we're totally aligned when it comes to the product, the vision and the benefits this union will deliver to the research community."

After the acquisition was announced, William Gunn, Mendeley's head of academic outreach, summarized the reaction on his blog: "There are and will be a couple competing narratives: They bought us to bury us, we got paid tons of money so we said, 'Fuck Open Access,' etc. This is going to be put in the context of Google Reader shutting down, Delicious 'sunsetting,' etc." He wrote, however, that, "I'm not personally getting a pile of money from all this, and I never would have stayed unless I was convinced that they legitimately want to be part of the change to an open access publishing system."

While a number of users vowed to flee Mendeley for other reference management software, open source alternatives like Zotero remain scarce and underfunded. Scott Cowley, a PhD student social media and digital strategy at Arizona State University, described the problem in a comment on Danah Boyd's blog post: "Until there's a non-profit project that goes to bat for the academic community, I don't see being able to avoid tradeoffs whether in technology or philosophy."

Takats doesn't keep careful track of Zotero's user numbers, he said, so he can't be sure if there was a mass exodus from Mendeley to his software. Takats isn't focused on revenue: The project makes enough money to sustain itself by selling storage space, and he doesn't work on it full-time. It's just a side project, he said.

The Elsevier Era

Post-acquisition, Mendeley has relaunched its API, the stream of data that allows any developer to dig into its thickets of data; Henning is proud that Elsevier's PDF previews and abstracts are back in it. "Anyone is welcome to take our API and come up with a better system."

Still, open science advocates don't think an API makes Mendeley open enough. Said Takats: "There's a difference between open source and an open API."

To really reform research, Henning said he's taken up a new mission: Fixing the process of peer review, in which submitted articles are first carefully critiqued by researchers in the article's subject area before publication. Open access research hubs like arXiv and the Public Library of Science (PLoS) have sought to remedy this in recent years. In the near future, peer reviewers will be able to annotate papers and see the other reviewers' comments directly in Mendeley, before publication. "The editor of the journal would receive all of these comments by email and would just send them all to the paper's authors. The comments would overlap and sometimes contradict one another. We're eventually going to avoid this," Henning said.

Another volley against tradition could come in the form of a new Elsevier acquisition, a London-based news-tracking startup called Newsflo. Its software could offer Mendeley users a way to track their research's impact across the web, and become a new way to gauge success. This kind of alternative metric is one of open science's ways of rising up against the traditional journal citation system, where a journal's influence alone can make a researcher's career.

Another new initiative by Mendeley and Elsevier is also aimed at the open science community. This past December, Axon hosted a group of 15 science startups at the LeWeb conference in Paris. Elsevier covered the more than $1,000 conference fee for each startup that came.

Transcriptic, a Silicon Valley-based life sciences startup, attended LeWeb on Henning's invitation. Max Hodak, Transcriptic's CEO, notes that the life sciences business community is pretty small, and any opportunity to meet other startups is valuable. "I know these are people that will be doing important things down the line," Hodak said of the other participating startups.

One of the other startups that participated in the LeWeb conference through the Axon program was The Winnower, a Virginia-based science publishing startup. Josh Nicholson, its CEO and cofounder, doesn't even use Mendeley. He has spent most of his academic career using competitor EndNote.

But "it's a pain to use," Nicholson said. Soon, he thinks, he'll switch over to Mendeley.